Dating women for the first time at 35

The terrors of pursuing intimacy over performance, and how we turn life into fiction.

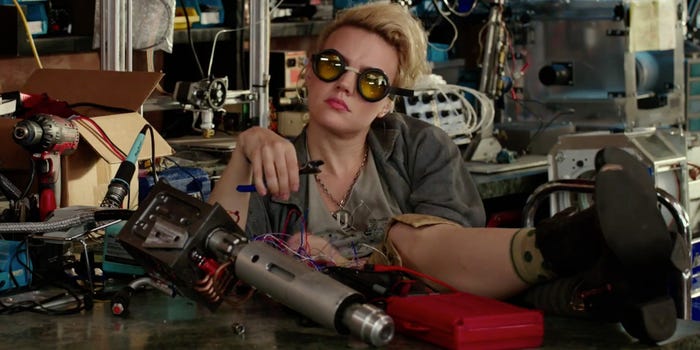

The first time I made out with a woman I was thirty-five and terrified. We had just finished seeing a movie, the Ghostbusters remake, which, as my dream woman would be wont to do, she’d already seen twice. Following the movie we went to a bar. In an oversized booth, leaning in to hear each other clearly, I admitted that I’d only ever slept with men, that she was only the second woman I’d gone out with. That I was terrified to go out with women because, among other things, I was afraid to admit that very thing. That it had taken me this long to figure out my sexuality, and even that wasn’t quite right—it had taken me this long to start to try and maybe figure out my sexuality.

But despite my awkward admissions, conversation came easy. She nodded as I stumbled, laughed at my self-deprecating jokes. When I glossed over an answer she challenged my empty phrases with witty jabs or thoughtful questions. There was self-assurance in the way she spoke that felt masculine, except that her emotional perception was unlike any man. This combination of confidence and empathy mixed with humility and understanding was like my own personalized love potion. She had only ever dated women, she said, and in that moment it occurred to me that the best version of a woman may be one who was unconcerned with men.

I moved my hand towards hers at the bar, but stopped halfway there, opting to grip the moist coaster in front of me instead, tearing the printed top off the cardboard circle. It was, I’d realized, impossible for me to decipher between friendliness and flirting with a woman. I’d had no practice and the last thing I wanted to do was make a move, like a creep, if she was simply being friendly.

I could always tell when a man found me attractive. This mostly happened when I made him feel attractive. It was an easy trick. I’d comment on an album, pick a favorite from the last guy I’d dated, or a book, Moby Dick or East of Eden, say, and his eyes would light up. I was repeating his tastes back to him, tastes I’d learned from the men I’d studied over the years, and this would make him feel validated, wanting more. But I couldn’t remember the last time I’d felt attractive simply by being honest. It’d been a long time since I’d let myself try.

It wasn’t until we were outside, lingering nervously by the subway stop like the end of every other New York date, that we kissed. She was short, around five feet. Having made a point to only ever date tall men in order to ensure—in my 5’9, curve-less body, draped strictly in t-shirts—that I’d feel at least a little bit feminine beside them, I felt nothing short of a monster hovering above her. Still, I liked her and so I invited her over.

By 10 pm she was straddling me on my couch, thick sheets of hair slapping me in the face. Her height was distracting, her thick hair, while mine was as thin as thread, intimidating, but her openness and desire was what scared me most. There’d been a kind of performance with men that I’d grown used to, the goal of which was not pleasure per say but the accumulation of power, a form of approval from the type of person I’d subconsciously learned to need approval from. Like so much of my life up to that point, going through the motions of chasing validation allowed me to side-step the deeply uncomfortable process of untangling what it was I actually wanted.

***

In college, the period of time when many begin to explore their sexuality in earnest, for some reason I doubled down on mine. Studying engineering with mostly men, long before social media was a thing (but when shows like Girls Gone Wild and The Man Show were very much a thing), the only time I saw women being romantic with other women was when they were vying for boys attention at the bar. This kind of overt performance for men was so off-putting to me—probably because at that point my entire existence was a subconscious web of covert performances for men—that I shut the idea of being with a woman out of my mind entirely. Two women together gave men pleasure, I reasoned, and I did not want to perform for men’s pleasure. I was oblivious to the now obvious irony that in this attempt at denial I was continuing to prioritize men’s reactions over the exploration of my own.

A decade of hetero-disappointments passed. Only in my thirties, as I started to dig deeper into who I was and what I wanted, detach from the all-male environments I’d professionally grown up in, did I begin to notice my attraction to women. It helped that dating men was becoming unbearable. As the reach of feminism expanded across culture, the ways I instinctively contorted my personality to make men comfortable was increasingly apparent—laughing when things weren’t funny, reflexively filling the holes in our conversation, asking question after question that I knew the answers to or didn’t care to know the answers to, to fill the silence. Men were finally being called out for their insufferability, terms like “mansplaining” popping up to describe behavior I recognized but had never considered naming.

I wasn’t attracted to the women I crushed on right away. It happened slowly as I got to know them. But was I attracted to the men I liked right away? Or had I simply learned after years of trial and error what kind of men I ended up working with and so a light went on when I saw their type? I had no idea what my ‘type’ was with women. Flirting with them made me feel awful, disgusting, even. Immediately, I mapped it to the hetero dynamic I was used to, picturing myself as a creepy, pushy guy. The women I liked were kind and open, to then try to convert that openness into something sexual, contorting their vulnerability for my own pleasure felt despicable. It was hard to imagine that maybe we were just two people enjoying one another, two equals with equal capacity to accept or reject.

So I did nothing.

Well, not nothing. I did what any person who is not comfortable with their emotions or human interaction in general does.

I opened an app.

Settings

Sexuality

Straight - Gay - Bisexual…

Bisexual

The word felt strange, too exploratory. It implied an openness to sex, not an instant fear at the thought of it. But there was no box for “Likes women and maybe wants to build up the courage to sleep with them but is also attracted to men even though she kind of hates them” so “bisexual” was it.

A new pile of smiling faces appeared on the screen. I always cringed at the cataloguing of people, but this time it was worse. I was used to looking at men this way, quickly assessing their height and eyes and the way they smiled. It was gross and judgmental but, I’d reasoned, it was nothing compared to the objectification women dealt with daily. This little window of objective browsing was a limited and optional experience for men not a constant grating pressure. Now, swiping through women, I was another person judging them, dismissing their whole person because their eyes seemed a little distant, or smile a little insincere.

The thought came and went as I closed the app. It was as if I couldn’t imagine sex with women because I liked them too much. I know women can be brutal, cause all kinds of heartbreak, but I hadn’t yet operated on that plane. And the experience I equated with sex at that time, a kind of transactional exchange of power and approval felt impossible to imagine with a woman.

Fears raced. Afraid I’d need to re-learn the fundamentals of intimacy, afraid to burden a woman I cared for with the help I knew I’d need. With men, I was happy to be reckless, jump into situations I knew wouldn’t work. I didn’t care if I hurt them, I’d been hurt by them my whole life. But I was terrified of disappointing a woman. And even more afraid of her rejection. There was safety in my failed relationships with men. I was happy to blame them, avoid the role I played in my own singleness. But if I failed with women, where would that leave me?

Life as Fiction

I wrote the bones of this essay almost seven years ago but never published it. Since then, I’ve woven these feelings and experiences into my novel.

Some readers of Nothing Serious have said they can’t understand how a woman can be in her mid-thirties and not know who she’s attracted to, that it feels unbelievable. It’s always funny to me when people say fiction is unbelievable without knowing that the very parts they’re referencing are pulled from life.

This is right under the wire for June, but HAPPY PRIDE to everyone out there celebrating, exploring, or even just contemplating their queerness! 🏳️🌈

Recommendation:

This article about the academic study of heterosexuality (specifically the “tragedy” of it) circulated months ago and I haven’t been able to get it out of my mind since. So much here, might write more about it later.

“The straight culture she observed relied “on a blind acceptance that women and men do not need to hold the other gender in high esteem as much as they need to need each other” and “to learn how to compromise and suppress their disappointment” in one another.”

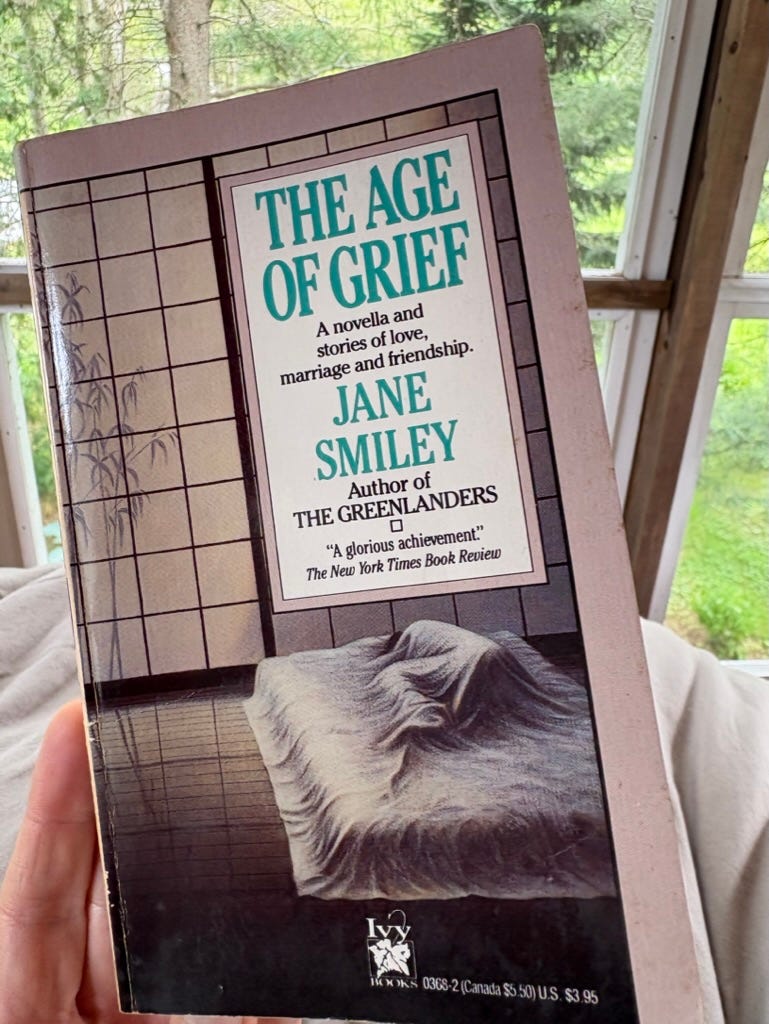

I’m dog-sitting my favorite doggies this week in the Adirondacks, and picked this off the extremely well-stocked wall of classics where I’m staying. Already blown away by the first story, The Pleasure of Her Company, which happens to relate to this post!